In Safe Hands: How to be a good advocate for your child with TSC at school

Sending your child to school for the first time is nerve-wracking for most parents. As a parent of a child with TSC (Tuberous Sclerosis Complex), there is often an extra layer of anxiety. Whilst not all children with TSC have learning difficulties, you may be concerned about making sure that your child feels adequately supported to do well at school and reach both their academic and social potential, particularly if they learn differently.

Download a PDF of the guide by completing the form below.

This advocacy guide for families is part of TSA’s In Safe Hands series, which also includes a guide for teachers and educators of children with TSC. Our goal is for families to feel they can trust their child with TSC will be ‘in safe hands’ during their school years and feel their child will be understood and supported both physically and emotionally.

Out of necessity schools have to work within a prescribed system and teachers and educators are always balancing a range of competing, complex demands with many of the children in a class having a range of needs which may not be obvious.

This guide provides information on how you can be an effective advocate for your child with TSC at school. Whilst every child with TSC is unique and every circumstance is different, we hope it will provide you with useful suggestions for how to get the best help and interventions to ensure your child’s needs are met. The guide is available below on this website and as a downloadable and print-at-home pdf. (Please note that some additional resources on this website are not in the pdf.) We sincerely hope that this guide is useful to you.

How to be a good advocate for your child with TSC at school

If you have a choice – and many families, particularly in rural areas, don’t – you will need to consider where you want to send your child to school. This will partly depend upon the sort of support your child needs at school.

Things to consider:

- Give yourself as much time as you can to plan. Many families recommend starting this planning years in advance.

- Collect as much information as you can.

- Visit local schools, speak with school principals, attend open days, speak to other parents with children at the school, use the My School website and talk with the school’s learning support coordinator.

- If your child has particular communication needs, discuss these before selecting a school.

You should share your child’s health needs and provide evidence of your child’s learning needs so that the school can prepare to support these. Discussing your child’s needs early provides time for the principal to apply for funding if necessary. A good question to ask the principal can be:

- ‘How will you support my child?‘ or

- ‘What kind of support do you currently access for children with learning needs?‘

This encourages the school to tell you how they will help rather than you telling them what you need. Be willing to listen to how much support the school can provide for your child. Schools and teachers have the best of intentions but most have limited resources.

Remember too, that education is about much more than just academic learning and you should consider how a school can also support your child in areas such as the arts, sports, social interactions and what other opportunities it can provide for your child to thrive and succeed.

There is no one best setting for all children. You must consider the learning environments and resources available in your community. Then, you can make a selection that you believe best matches your child’s needs and circumstances. It’s also important to periodically re-evaluate your choice as your child’s needs and circumstances may change over time.

For more information on choosing a school visit Raising Children

Mainstream versus supported settings

If your child has disability and/or moderate to high support needs, there are extra things for you to think about. You may need to consider whether your child will thrive best in a mainstream or more supported setting.

‘Mainstreaming’ means including children with learning difficulties and disabilities in regular classrooms. They get the same opportunities as any other child to enjoy every aspect of the school experience. In this setting children often learn important life skills and there are many rewarding opportunities for socialisation. Of course, a successful mainstreaming experience requires adequate resourcing and also depends upon the educational system, the school and your child.

Some mainstream schools also have special classes for children with mild to moderate learning and support needs. These support classes have specific enrolment criteria and application processes. They provide smaller class sizes and more staff to help children learn the skills they need and to socialise with their peers in the playground. Demand for placement in these classes is usually high and, whilst application guides vary from state to state, you often need to start the process in the year before your child is due to start school.

Schools for Specific Purposes (SSPs), known as special schools, provide specialist and intensive support in a dedicated setting for children with moderate to high learning and support needs. They also have specific enrolment criteria that your child will need to meet. SSPs support children with intellectual disability, mental health issues or autism, physical disability or sensory impairment, and learning difficulties or behaviour disorders. One of the biggest differences between mainstream and special schools is that special schools have a higher staff to child ratio. Special schools are already resourced to provide the extra support and attention that a child with learning difficulties and disabilities may need.

Special schools can cater for a child with complex needs. They may have nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists or they will work with your NDIS provider. Some have hydrotherapy pools. As well as teaching the Australian curriculum their teachers are trained to meet the social, emotional, medical and behavioural needs of students.

Not every community will have support classes or special schools. You will need to consider whether and how far you want your child to travel to get to school.

For more information on education and disability visit Raising Children

Additional supports in mainstream schools

Mainstream schools receive funding for ‘necessary adjustments‘, but not all children with additional needs are eligible for individual funding. Without appropriate support your child may fall behind and/or become unhappy at school.

When you first visit a school, you may want to ask about their specific experience teaching children with learning differences and disabilities. You might ask about their experience in using extra supports that may be recommended to help your child. These might include:

- Teacher’s aides

- Visual supports (such as a visual timetable to assist a child with autism deal with transitions or changes in routine)

- Use of sensory aides or movement breaks

- Alternative seating arrangements (if for example your child needs to sit or lay on the floor).

It can also be worth asking how they view the role of an aide in the classroom. A good teacher is one who sees the aide as an extra team member in the room, not somebody who is attached to the child. The teacher may sometimes ask the aide to support other children so that they can work directly with your child with TSC.

If your child uses an alternative or augmented communication device (AAC), you may need to advocate for support to be available to your child and their teacher(s), especially in a mainstream setting. It is important to ask questions such as:

- ‘How will teaching staff be trained in the AAC’s use?‘

- ‘How will my child access their device throughout the day?‘

You should find out whether your child will be supported to use the device to assist in socialising with other children in the playground.

The school counsellor and/or the learning support coordinator can be valuable assets to a child with TSC who has learning difficulties. It may be worth asking if you can meet with this person/these people. They can provide access to special programs such as those for children with anxiety. The counsellor and school principal are also usually responsible for applying for funding for any additional supports that your child needs.

As parents we want to focus on our child’s strengths. But, when seeking additional support, it is a good idea to imagine your child’s worse day and base the assessment on this. This can be a confronting process. But, the ‘worse-case scenario’ can really help prove why your child needs funding. Reports and input from the specialists treating your child should be made available to the school so they can best address the needs of your child.

You can get more information about the availability of school support and funding for your child from your state or territory education department:

- ACT Department of Education – Disability education

- NSW Department of Education – Disability, learning and support

- NT Government – About special education and disability

- Queensland Department of Education and Training – Students with disability

- South Australian Government – Learning plans

- Tasmanian Department of Education – Students with Disability

- Victorian Department of Education – Support for children with special needs

- WA Department of Education – Children with special learning needs

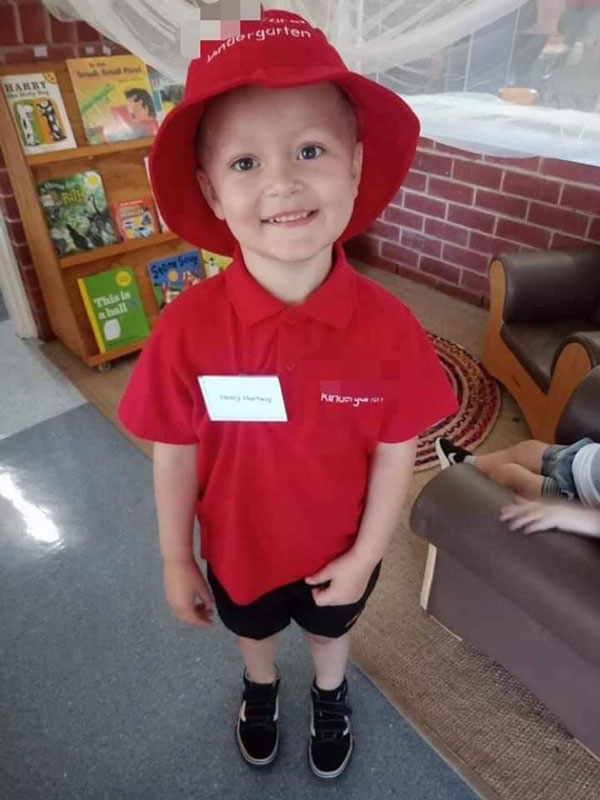

Our son Oskar is starting kindergarten in 2021. Deciding on the best school setting for him was a daunting task. We carefully considered mainstream and special school options. Through the help of our local school, we were able to enrol Oskar in a government run early intervention program. We were impressed with the dedicated support provided by our local school. We felt that if Oskar was to attend there, he would be in great hands. Considering Oskar’s moderate intellectual disability and medical needs, we felt it important to also look at special needs schools. St Lucy’s Catholic School came to our attention and we attended an open day. We were blown away by the facilities and specialised equipment but more importantly by the passionate, caring and positive staff. After learning that only a small number of spots were available in 2021, we had the enrolment papers filled out and submitted to the school within hours.

Before attending the open day, Oskar had a developmental assessment performed and further assessments with all his therapists to ensure we had current medical reports to supplement his enrolment application. Oskar then attended an observation day with staff at St Lucy’s. He came out beaming with excitement. It confirmed our feelings that this school was perfect for him. We then had an interview with the school principal and registrar who both felt, after observing Oskar, that St Lucy’s would be the ideal setting for him to begin his education. Finalising this decision has given us great peace of mind. Being organised, punctual and forthcoming with medical information gave us the upper hand in securing his enrolment.

If your child with TSC has epilepsy a Seizure Management Plan must be put in place. This can be provided (and updated) by your child’s medical team. It provides management strategies and guidance on supervision and safety.

It is important that you ask how the school will manage your child’s epilepsy:

- How will your child be monitored by staff?

- How will your child be cared for if they have a seizure?

- Are there staff who are already trained in epilepsy management?

You need to have confidence that the school will make training and support available to staff who have to deal with the management and treatment of seizures. You may need to take the lead in arranging epilepsy training for staff.

Epilepsy training can be organised by the nurse/educator from your local hospital or a representative from a national or state-based epilepsy organisation such as Epilepsy Australia or Epilepsy Action Australia can provide professional education.

Individual education plans (IEPs), also called individual learning plans or learning improvement plans, assist children who need support with their education. This includes children affected by TSC. IEPs are written statements that describe the adjustments, goals and strategies to meet a child’s individual educational needs so they can reach their full potential. An IEP can help you and your child’s teaching team plan and track their unique learning needs. The best plan starts with and builds upon your child’s strengths and interests.

You should ask about IEPs when you first visit a school. The best educational setting is the one that helps a child to achieve their goals and caters for their individual abilities and needs.

It can be really helpful to engage your child’s therapists in IEP meetings so that goals are shared across settings and therefore re-enforced. If your child has a teacher’s aide, they should be included in meetings if at all possible. Many schools don’t include these people in planning sessions because they are not teachers and their role is to support the implementation of the teacher’s plan. However, they are often the ones that work one-on-one with your child and can have good insight as to how they are progressing.

Discuss your child’s interests and whether activities can be built around these. For example, if your child loves My Little Pony, then simply adding some My Little Pony pictures or icons into the work can get them interested and hold their attention.

Some children with TSC will have problems associated with specific language delays. Make your child’s teaching team aware of how your child communicates. These ideas may help:

- Let the teaching team know if your child is attending speech therapy.

- Ask if your child’s speech therapist can meet with the teaching team to discuss your child’s therapy goals and the best way for the team to encourage and develop your child’s communication.

- If your child uses visuals or sign language, talk to the school about teaching staff and other children learning these communication systems.

- If your child uses an AAC device ask about AAC training for the team. Find out how your child will be supported to use the device to assist in socialising with other children.

- If your child is given supportive technologies to assist with learning at school, it is important that both they and you are shown how to use these.

Monitoring of the IEP should take place often and actively. The IEP meeting is a chance to set up strategies that work for your child. It should not feel like a ‘ticking the box’ exercise. Meet regularly with the school learning support team and your child’s teaching team, including, if possible, any aides who work with your child.

At the very least, an IEP meeting should take place near the start of every school year.

For more information on IEPs visit All Means All

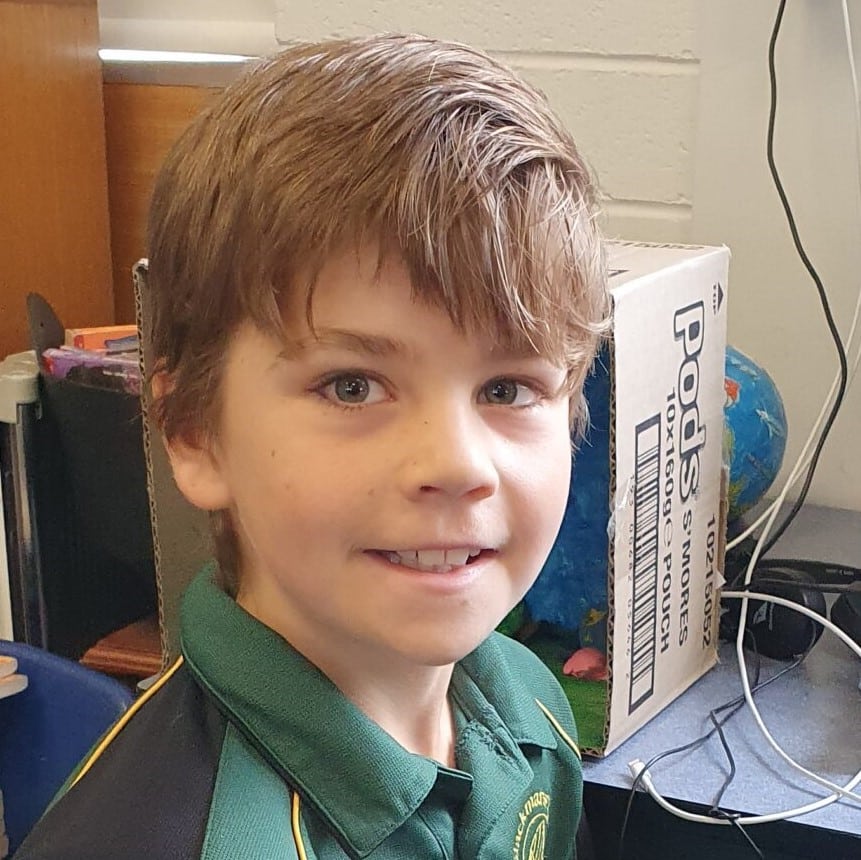

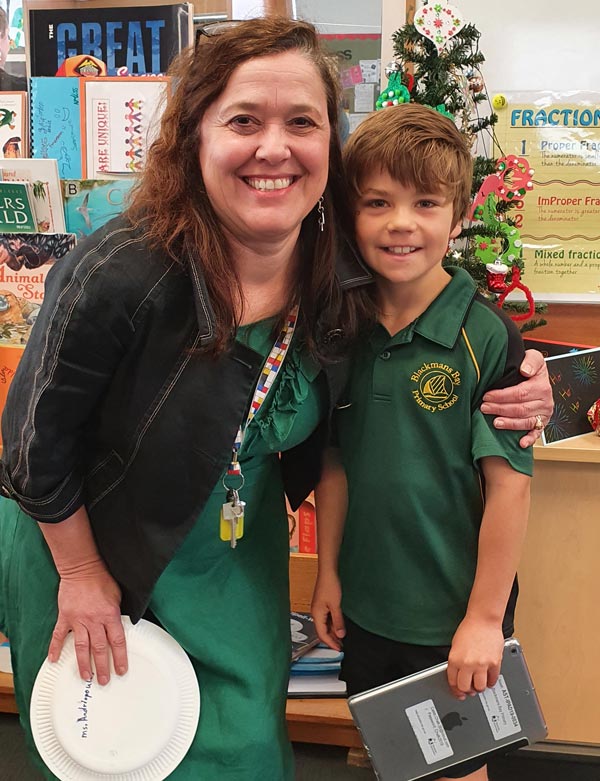

Caleb was put on an Individual Learning Plan last year. This came about due to his TSC diagnosis initially and now with his dyslexia diagnosis as well. These meetings have sometimes felt like a ‘ticking the box’ exercise. The reality is that classrooms are busy so it is up to us to set up strategies that work for Caleb. A useful tip is to have notes written down on how you think your child is going and any feedback and suggestions you want to give. This can keep the meeting on track and makes the most of the time. It is so important to speak up if you are not happy about something as hard as this is sometimes.

One thing I did at Caleb’s initial learning plan meeting was look at the TSA website together with his teacher and the support teacher. This seemed to have more impact than simply giving them the web address. A lot of questions and discussion arose from looking at the website together. I found the TAND questionnaire to be a very useful resource. It helps explain the importance of monitoring children with TSC and how things can change.

Schools are busy places. Resources and time are often stretched as the teaching team juggles the competing demands of their exceptionally challenging roles. Your goal should be to build and maintain a positive, constructive relationship with your child’s school. Try to find a school principal, teacher and/or learning support coordinator you have some rapport with and who you feel you can trust.

Learning to advocate for your child can take time. You may have your ups and downs in your relationship with your child’s school. Even during tricky times, it’s importatnt to remain positive. Having an ally at the school such as a counsellor or coordinator can really help.

Helping the teaching team understand TSC and how it might affect your child’s learning

Your child might be the first child with TSC who has attended the school. Even if that is not the case, you will want to share information about TSC and how it affects your child.

You might suggest holding a teacher briefing session and/or looking at the TSA website together. Other families have found this can be more effective than simply providing the web address as it opens up the opportunity for questions and discussion.

The school counsellor and/or the learning support coordinator can be valuable assets to a child with TSC. So too is a teacher your child connects with, who is willing to act as a mentor. These people may be happy to be involved in, or even run, briefing sessions about TSC for the teaching team.

The school will probably already have experience teaching children with autism, ADHD, language delay, learning difficulty and epilepsy. Explaining how children with TSC may share some of these same characteristics can be helpful.

Make the teaching team aware of TSA’s In Safe Hands: An introductory guide to TSC for teachers and educators or print out copies for them. The teachers and educators guide includes information about possible learning difficulties that a child with TSC may be affected by.

Make yourself available to answer questions and provide information. TSC is one subject area where you will have more expertise and knowledge than any of your children’s teaching team, so don’t be afraid to share it with them!

Giving information to the teaching team about your child

Focus on what the teaching team really need to know about your child.

What will or could affect their performance in a classroom? Schools have a lot of children to get to know and understand, so it’s important that your communications are concise and clear. It’s also a good idea to clearly separate medical needs from learning needs.

At the initial IEP or parent/teacher meeting discuss any behavioural, physical, intellectual, learning or mental health challenges your child may have. These challenges may affect the way your child learns in a classroom setting and have an impact on the way they are taught. For example, if your child is having difficulty sleeping this may have a big effect on behaviour and learning and the teaching team need to be made aware of this. You could also share what causes your child anxiety or pain. If you are aware of physical activities or rituals that can be calming or arousing and support your child being in the right state for being safe and learning-ready, then make sure your child’s team know about these. This can be critical information to help your child. See the Template: Personal information form for a child with TSC for an example of the sort of information you might provide. Medications are best noted on a separate page so that that updates can easily be made. Some parents have also included a photo of their child, the latest letters from their TSC health professionals, assessment reports, etc, but you will need to discuss with the school whether this is useful to them and also carefully consider privacy and confidentiality issues.

If your child has other professionals such as an occupational therapist, speech therapist or psychologist in their team, you may be able to arrange for them to visit the school to help the teachers understand your child’s needs. The visits of therapists could be built into your NDIS plan to cover the cost of consultation with schools or at least the cost of reports.

Even if that is not possible, sharing reports from your specialist team can also assist the teaching team. For example, you may have a recent neuropsychologist or speech therapist assessment that highlights where your child is struggling as well as their recommendations for strategies to assist your child in meeting their goals.

Deficits are not always obvious. Children with TSC can have glaring deficiencies in very specific areas, and these need to be made clear to the teaching team – usually at IEP meetings. Cognitive and learning assessments and/or the TAND checklist can be useful. It is important to track children with TSC and notice how things can change over time.

Almost 90% of people affected by TSC will suffer from one or more TSC associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) over their lifetime. The level of severity varies widely. TAND can affect a child’s quality of life and, their education and learning. Again,the TAND Checklist is a helpful screening tool.

TAND can impact six areas

Behaviour

Children with TSC may have some of the following behaviours of concern:

- Aggression

- Explosive behaviour

- Inattention

- Self-injury

- Anxiety

- Extreme shyness

- Poor eye contact

- Sleep-related issues

- Depressed mood

- Hyperactivity

- Repetitive behaviours

Psychiatric

Examples of psychiatric disorders children with TSC may be affected by include:

- Anxiety disorder

- Depressive disorder

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Intellectual

Learning problems in children with TSC may include:

- Intellectual disability

- Language disorders

- Uneven intellectual profiles

Academic

Children with TSC struggle most commonly in the following academic areas:

- Mathematics

- Writing

- Reading

- Spelling

Neuropsychological

Some children with TSC may struggle with one or more of the following neuropsychological issues:

- Attentional switching

- Memory recall

- Cognitive flexibility

- Spatial working memory

- Dual tasking

- Sustained attention

Psychosocial

Children with TSC may have difficulties dealing with:

- Parental stress

- Self-esteem

- Relationship difficulties

- Self-efficacy

Working out the best way for you to communicate

As well as working out what you need to communicate with your child’s teaching team, you also need to work out when, where and how communications should best take place. Consider:

- What works for both you and your child’s teaching team?

- Do you need to book time in advance to speak with them?

- Is a quick chat at the end of the day OK?

It can be useful to have written notes on how you think your child is going and any feedback and suggestions you want to give. This can keep meetings on track and makes the most of the time. It is so important to speak up if you are not happy about something and this can sometimes be a really hard thing to do.

There are so many ways to communicate these days. Sometimes something as simple as a handwritten book or a brief daily email update from a teacher can be so useful. Notes can be written on how the day has been and any other information. This can be really useful if your child has part-time aides, which can often be the case, or if the aide is away and they have a relief aide. The more informed the aide is, the better the outcomes for everyone.

Your goal is to become a valued member of your child’s support team. Your child will get the most out of their time at school if you and their teaching team can communicate well and often. This is especially important if either of you notices changes in your child’s behaviour.

What I have learnt from my journey with Max through school is that some teachers are naturals at working with kids with ‘issues’, others can learn and there are the odd few who just don’t get it. The school counsellor at both the primary and high school have been my ‘go to’ person for any issues. I always made myself available to school staff. This became a problem as the school was ringing me for every issue Max had. This year my approach has been to work with Max’s occupational therapist to develop goals that he is working toward, one of which is establishing his independence. He doesn’t like the school involving me in every issue. I have now worked out a system where he has a teacher who has taken him under his wing and acts like a mentor. It is very important for Max to have that connection with a teacher and this is something the school counsellor understood. She was very adept at providing Max’s teaching team with a briefing session about TSC every January before school began. She was also instrumental in providing input into subject and teacher selection for Max in his final years. Max and I have been lucky in finding people both at primary school and high school who really connected with him and had a genuine interest in helping his education. Persistence is the key.

Adapting to staff changes

Some parents may find it challenging when changes are made to their child’s teaching team. Although this is out of everyone’s control, it can be very frustrating. Developing a positive relationship with the whole teaching team increases the chances of information being passed on to new teachers or educators who work with your child. Having a ‘ready made’ pack with your child’s information (such as a completed and up-to-date Personal information form) that can be given to any teachers and teaching staff who may work with your child may also be useful.

Your child’s classmates

Sometimes the teaching team are not the only ones who need to understand your child’s medical condition. In some instances it might be helpful for your child’s classmates to understand TSC. Talk to the teaching team about how you and they might explain TSC to the class. You might share the TSA video Meet Abby. For infants and younger children TSA’s picture book A Little Book About TSC can be a good starting point.

Being flexible and realistic

Your child has a legal right to attend your local school and the school has an obligation to provide your child with an education. But, you must be realistic and flexible. Most schools have stretched resources and limited time to balance the needs of many children and parents. Sometimes you may need to take a step back and consider whether your expectations are fair and reasonable for the school and its teaching team.

Noticing the good stuff

Everyone loves and responds to praise. Your child’s teaching team will be more receptive to discussing improvements if you acknowledge what they’ve done well. Start conversations with thanking them for something they’ve done that’s great. Let them know that you need to hear positives as well. Teachers may focus on what your child doesn’t do well, especially with challenging behaviours such as ADHD which can be disruptive in the classroom. This can create an environment of negativity. Remind the teaching team that positive reinforcement is helpful. And, try to look beyond the behaviour to determine the triggers, so that strategies can be put in place to improve learning outcomes.

Not being afraid to try other options

If your child becomes unhappy or unsettled, or their needs change, consider alternative options. The solution may be extra tutoring, changing schools to a setting that better supports your child’s needs or even distance education.

Work out what’s really important for your child and advocate for it. Be respectful but persistent. It can take months and even years to get it right!

Involving your child

Finally, and very importantly, if it is at all possible, find a way to give your child some choice and control over what helps them at school. Doing this right from the start will involve them and help them feel invested in the choices that are made. It also helps them learn the skills needed to speak up for themselves as they grow up. If the school is ringing you about every issue they have, your child may not like this, so consider if there are ways you can support your child to be more independent.

Selecting a high school

The high/secondary school environment can pose fresh challenges for a child with TSC. Look at the available high school options. Consider which school your child would like to go to and seems to best suit their unique needs. For some pointers, see Steve’s story about Liam below.

Transitioning to high school

The transition itself can also raise new and different issues, especially in a mainstream school, where your child will typically now have to move from class to class and have many more teachers. In a mainstream school in the lower years, your child could have more than 10 teachers (including a year level coordinator, form teacher, different subject teachers as well as other teachers for sport). Year level coordinators and form teachers can be helpful in sharing information to other teachers, but this certainly doesn’t always happen.

Another complicating factor in secondary school years is adolescence. This can cause changes to TSC-related symptoms or the severity of symptoms. For example, a child who has achieved seizure control during primary school may find themselves subject to seizures during adolescence. This may also mean a change in medications.

Year level coordinators and form teachers may be useful allies. Some parents have found the transition worked well when they had the school counsellor or learning support coordinator of both the primary and high schools as their ‘go to’ person for any issues. Anticipating changes and working with both schools will help to support your child’s successful transition.

The school counsellor or learning support coordinator can also provide useful input into subject and teacher selection for your child in high school. You should speak to individual subject teachers where your child is likely to have problems (eg in Maths, languages and English).

Our son Liam has a TSC2 mutation. He had infantile spasms. He has controllable focal epilepsy (he is on keppra), mild autism, ADHD (inattention), poor working memory and very slow processing speed. As Liam likes to follow rules, we’ve often been concerned that some people, including teachers, may inadvertently overlook his deficiencies, and not realise he’d lost track or didn’t recall the first steps of a task.

Liam had a fantastic experience at his special preschool which catered for all children including those with additional needs. He had on-site help from speech therapists and occupational therapists.

After preschool, we had the choice to send him to the local K-2 infant’s school or to the K-6 primary school. Remarkably, the local infant’s school instantly and dismissively responded that they could not cater for a child with additional needs. The primary school’s response was the polar opposite. The principal sent two kindergarten teachers to Liam’s preschool to assess his needs and talk with him and his preschool teachers. So, whilst the idea of a smaller, potentially gentler school appealed to us, we realised that the larger school seemed better equipped to deal with Liam’s needs and had access to greater resources. Not surprisingly, we enrolled Liam at the primary school.

Liam enjoys school. He likes his teachers and routines. He has struggled with anxiety at times (particularly on stormy days) and making connections with his own peer group (he’ll tend to gravitate to the sandpit with the younger kids). Even though he enjoys choir and drama group, often he chooses not to go. Despite the occasional challenges, being able to stay in a familiar environment at the same school has been a great benefit to Liam.

We are fortunate that Liam has had the support of a teacher’s aide, particularly in these later years. We’ve asked his teachers to use the aide creatively. For instance, the aide works with other groups of children freeing the teacher up to explain concepts to Liam. We feel lucky to have been able to access the level of support he has. Our application to the Department of Education proved pivotal. Liam’s mum Kate attended a Positive Partnerships course which introduced us to a planning matrix.

Apparently the Department of Education was so impressed with Kate’s matrix outlining Liam’s strengths and weaknesses in terms of communication, behaviour, social interaction, sensory processing, learning styles and information processing, that they said they would revise the whole application process!

Liam has an IEP. We have met with his teacher, the principal or deputy, the support coordinator and the school’s psychologist at the start of each year. This meeting has provided a good opportunity to talk about his TSC diagnosis, his particular individual needs and set up a plan for the year ahead. Throughout the year any concerns we’ve had have usually been addressed via email. At the end of each year we have discussed with the school who his teacher will be and which supportive friends he might share a class with in the following year.

To Liam’s dismay he is now at the point where he is going to have to change schools to go to high school. He’s been adamant to the point of tears that he doesn’t want to go to an all boys school. Unfortunately, our local public high school gave us no confidence that they would be able to meet Liam’s needs, giving very defensive answers to our questions. So we looked around, attending many open days over three years. Our overall positive experience of public education led us to look at out-of-area high schools. As Liam is quite creative and often gravitates to arts and crafts, we helped him collate a portfolio of his art for an application to a specialist arts high school. He strode into the interview looking so grown up and waltzed out with so much belief in himself. Whilst he wasn’t accepted into the specialist stream, he was accepted as an out-of-area mainstream enrolment, which seemed like a miracle and was a huge relief. This high school focuses on creativity and emphasises inclusion, humour, uniqueness and deliberate acceptance of difference and quirkiness. We are really hopeful that Liam will find his tribe.

As parents of a wonderfully unique child we’ve often been overwhelmed by the process of choosing a high school. Here are a few things we’ve learnt:

• It was worth going to as many open days as we could, with and without Liam.

• Once we thought we’d decided on a school we enrolled Liam in after-school activities of interest to test it out, eg, a robotics course for primary students with the high school science teacher.

• Asking everyone we could (especially those who know Liam) for their opinions, or lack of, proved insightful.

• Questioning the high school principal and teachers often exposed when they were deviating from the Department of Education’s ‘script’, which we often saw as a weakness. For example, we found it reassuring when the principal was able to clearly state the procedures in place to deal with bullying rather than claim it wasn’t really a problem at their school.

• Writing a succinct letter to the high school outlining why we felt the school was right for Liam and asking his primary school principal to do the same (on top of the standard application documents) may have helped.

• We could overload Liam with our expectations and confuse him with options. It was often best not to have him look too far ahead.

• Trusting our, and Liam’s, gut instincts about a school was important.

Liam has been fortunate and is now excited about the change. It’s wonderful to see the glint in his eye when he excitedly tells his primary school teachers that he made it in and he’s going to high school!”

Every child is unique and TSC affects every individual differently. Every family’s and child’s experience of school will be specific to them. It is unlikely that everything in this guide will be relevant to you and your child, but we hope you have found some of the information and suggestions useful.

As the stories in this guide from the parents of children with TSC show, there are some great schools and excellent teachers in Australia who create positive learning experiences. That said, advocating for your child with TSC may not always be easy. There may be times when you feel misunderstood or that you are not succeeding. Some parents say they feel like they have the same conversations over and over again. There may be times when you feel you have to justify yourself. It may feel like you are in an endless cycle of guilt, shame, anger and tiredness. It’s really important to have your own supports in place, so that if the going gets tough, you have someone or somewhere to turn to.

It’s hard for me being in my position…a mother of a son with special needs and also being a special education teacher. I am in the position of caring for other people’s children with high medical, physical, behavioural and learning needs. I support parents like myself. I ensure they understand that I will do anything I can for their children. I want their needs met and I want them to be successful. I am a constant support for parents who are in difficult situations and the challenges that come with disability. YET I STRUGGLE to be these parents…I struggle to advocate for my child, I struggle with the education system…I cry at meetings!!! Yet I can be stoic and advocate strongly for others…for the children in my care. It’s easier I guess when they are not your own. I feel like I fail all the time. I get tired. These are the challenges we face as parent advocates of a child with TSC. It can be difficult and not always rewarding to have to advocate. Sometimes it feels like it makes no difference at all. But, if we don’t do this, our child’s education and learning will suffer. For me, that’s just not an option.

This is a (fictional) example IEP document for a child with TSC. This example takes into account the learning needs and issues of the child with TSC. The Content Descriptors have been taken straight from the Australian Curriculum. The Learning Expectation is the personalised goal that teachers would write for the child. The Strategies are what or how the teacher would use to support the needs of the child and their learning.

The IEP is modified and individualised depending on the challenges each child has related to their TSC.

For example:

- For a child with specific learning disorder/dyslexia, the teacher might document the types of supports they would use in the ‘strategies’ section to allow the child to still achieve and show their knowledge of the curriculum.

- For a child with epilepsy, the teacher might document strategies such as 1:1 support, watch for fatigue, check for seizure activity, repeat instructions and check for understanding.

- For a child with Autism Spectrum Disorder they might include strategies such as wait time, use of visuals, 1:1 support.

Sample IEP template (PDF)

Last updated: 30 January 2023

Additional information

For more information on TSC, visit TSA’s website at https://tsa.org.au

You may also like to call TSA’s Nurse Service on 1300 733 435 (Australia only) or email [email protected]

Acknowledgement

TSA would like to acknowledge that some material used within this resource was based on the ABC Life article, Being the best advocate for your child with autism at school

Some materials are also adapted from and used by permission of the TSC Alliance, USA. We would like to thank TSC Alliance for its generosity in sharing its expertise and knowledge with us.

We are also indebted to the many families of children with TSC, health professionals, teachers and educators who have been involved in the development of this Australian-based resource.

TSA would also like to acknowledge that publication of this material would not have been possible without the financial support of our TSC community, the Disabled Children’s Foundation (DCF) and Universal Charitable Fund (UCF).

Disclaimer

This publication provides basic information about TSC (Tuberous Sclerosis Complex). It is not intended to, nor does it, constitute medical or other advice. Readers are warned not to take any action with regard to medical treatment without first consulting a health care provider.

©2021 Tuberous Sclerosis Australia (TSA)