Behavioural, Psychiatric, Intellectual, Academic/Learning, Neuropsychological and Psychosocial challenges

Key messages:

- TAND stands for TSC Associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders

- TAND includes (among other things) behaviour, intellectual disability, autism, learning difficulties and mental ill health

- The TAND checklist should be used annually to support screening for TAND

- More comprehensive assessment should be done at each developmental stage

- Management of TAND includes medicine and non-medicine based approaches

The impacts of TSC (Tuberous Sclerosis Complex) on behaviour, learning and mental health are often the most difficult symptoms of TSC for families to cope with. It is important that families, carers, educators and health professionals are aware of these challenges; look for them in the TSC affected person at regular intervals; and implement appropriate strategies to deal with them.

The term TAND has been coined for these challenges. It stands for TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorders. Other terms that can be used for these difficulties include ‘neurocognitive issues’, ‘neurobehavioural difficulties’, ‘learning issues’, ‘mental ill health’, ‘neuropsychiatric disorders’, ‘neurodevelopmental difficulties’ and ‘cognitive and behavioural difficulties’. We know there can be stigma associated with some of these terms, however most often there are no alternative words to use. For this reason we have chosen to use the terms used by doctors and researchers in this area of TSC.

This Information page is divided into the following sections:

- Signs and Symptoms that make up TAND

- Screening and Assessment for TAND

- Management of TAND

As with all TSA information pages, this information is not intended to, and it should not, constitute medical or other advice. Readers are warned not to take any action without first seeking medical advice. The best way to use this information is to bring it with you to your next appointment with your health professional.

Assessment and management of these signs of TSC can involve a number of different professionals:

- A psychiatrist is a medical doctor who specialises in the treatment of mental illness. Some psychiatrists will specialize in treating younger people, so may be called child and adolescent psychiatrists.

- A developmental paediatrician is a specialist in children’s development and behaviour. This includes how they acquire knowledge and skills, and how they learn to behave and socialise. Developmental paediatricians tend to specialise in disorders of development such as autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and intellectual disability.

- A clinical psychologist is a specially qualified psychologist who can provide assessment as well as treatment. There are many different types of psychologists and in Australia there are specific training requirements that need to be met before a person can call themselves a psychologist.

- Counsellors, social workers and therapists can have a range of different qualifications and experience.

- Special education teachers are specially trained to work with children who have special needs. They may be involved in creating individual plans, adapting teaching methods and equipment to suit the needs of the individual student.

Different professionals will describe different aspects of behaviour, learning and mental health differently. This can be confusing and people with TSC and their carers should ask for clarification if they are unsure what aspect of behaviour, learning or mental health is being assessed or treated.

How TSC causes these difficulties with behaviour, learning and mental health is not clear. It is also not clear why there is such a large variation in how different individuals with TSC, even those within the same family, are affected.

Researchers used to think that these difficulties were caused by a combination of:

- The number and position of tumours (tubers) in the brain

- The types of seizures, age of onset and whether the seizures can be controlled

However, as researchers have done more work, it has become clear that the molecular abnormalities caused by the TSC mutation can directly lead to learning, behavioural and mental health problems.

People with TSC who have infantile spasms and difficult to control epilepsy do seem to be at greater risk of developmental disorders including autism and intellectual disability. This is the reason that many neurologists will recommend an aggressive approach to seizure control, especially in young children.

Signs, Symptoms and

Treatments

Signs and Symptoms

The aim of understanding the different areas where a person with TSC may have difficulties is to identify the areas of strength and difficulties in each individual. This is done through regular screening and then assessment and testing. After these strengths and difficulties are identified the team of professionals can work with the family to work out what additional help may be needed to help the individual achieve their potential.

Different families will have different priorities and goals. Intervention should be individualised to meet the needs of both the person with TSC and their family.

It is important to remember that not every individual with TSC will have difficulties with every aspect of TAND. A diagnosis of Tuberous Sclerosis does mean that the individual is at an increased risk of difficulties in these areas at some point in their lifetime.

TAND can be understood by considering different levels or dimensions. These levels have been suggested by the Neuropsychiatry Panel at the 2012 International Consensus Conference. The levels are: behavioural; psychiatric; intellectual; academic; neuropsychological; and psychosocial.

The term 'behavioural difficulties' refers to the problems that can be observed at home, at school or in a clinic. Some examples of difficult behaviours that are common in people with TSC are:

- Poor eye contact

- Repetitive and ritualistic behaviours

- Inattention

- Restlessness

- Impulsivity

- Aggression

- Temper tantrums

- Self-injury

- Sleep difficulties

- Anxiety

- Depressed mood

- Extreme shyness

The behavioural level often represents a reason for referral by a GP or Paediatrician. A specialist team may then do a more comprehensive assessment.

Only some of these behavioural difficulties will be related to a specific disorder that can be diagnosed, such as an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism. These disorders are covered in more detail below. Diagnosis requires that a professional, such as a psychiatrist, developmental paediatrician or psychologist, use their expertise to assess the individual against the criteria for a specific psychiatric disorder.

For more on emerging challenging behaviours in children living with TSC watch this video with Dr Kate Thomson Bowe.

Some of these behavioural difficulties are more common in people with TSC who also have an intellectual disability. For example, some surveys of TSC affected children and adolescents with an IQ in the normal range show that about half will have aggressive behaviours and about half will have sleep problems. TSC affected adults with an IQ in the average range are at an increased risk of mood and anxiety disorders.

Sleep difficulties

Sleep difficulties can include:

- insomnia, which is difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep;

- sleep apnea; and

- restless leg syndrome.

Most researchers have found people with TSC, and especially those with an intellectual disability, are at higher risk of sleep disturbances.

It can be very difficult to identify the cause and find treatments for sleep disturbances in people with TSC. This can be because they are having night time seizures or because of side effects of anti-epilepsy medication. When an individual has an intellectual disability and/or communication difficulties this can make it more difficult to understand the cause of sleep disturbances.

Sleep difficulties can sometimes be improved through behavioural management and sometimes through medical treatment. Difficulties with sleep should be discussed by the individual with TSC (or their family member) and their health professional(s).

In this domain behaviours that cause concern are evaluated in the context of the person’s age, developmental or intellectual level and other characteristics. Some people with TSC will meet the criteria for a specific disorder defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) or the International Classification of Diseases, eleventh edition (ICD-11).

The most common psychiatric disorders experienced by people with TSC are:

- Autism spectrum disorders, experienced by between one quarter and one half of people with TSC

- Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders, experienced by between one third and one half of people with TSC

- Anxiety and depressive disorders, experienced by between one third and over half of people with TSC.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong developmental disability characterised by marked and persistent difficulties in social communication and interaction together with restricted and repetitive interests and behaviours including sensory sensitivities.

The largest studies into rates of autism in children with TSC find that approximately 40-50% of children with TSC have an autism spectrum disorder. TSC is now considered to be the medical condition most strongly associated with autism, even more than Fragile X or neurofibromatosis.

Diagnosis of autism includes assessment of two areas, in the context of the individual’s overall development and language skills:

- Social communications and interactions with others which can include difficulties in:

- social-emotional reciprocity, for example sharing of interests;

- nonverbal communication, for example eye contact; and

- developing, maintaining and understanding social relationships, for example playing, making friends or adjusting behaviours to different social environments.

- Restrictive or repetitive patterns of behaviour which can include:

- repetitive movements and use of language;

- ritual, routines and difficulties with transitions;

- interests which are unusual in their focus or intensity or interest in parts of objects eg spinning wheels of toy cars;

- over or under responsiveness to sensory input for example sounds, touch, light.

There is no one feature of autism that on its own can confirm or rule out autism. Autism spectrum disorder looks different in different individuals and especially varies with age, developmental skills and language skills. There is a wide spectrum of autism that ranges from very severe to very mild. This is the reason for the term autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

If a child with TSC demonstrates autistic behaviours it is important to seek a diagnostic evaluation. This is often the first step to receiving the appropriate services and support such as early intervention.

For more on ASD and ADHD watch this video with Dr Vinita Prasad, Developmental and Behavioural Paediatrician.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is usually first diagnosed in childhood and can continue into adulthood. Children with ADHD may have trouble paying attention, act impulsively (without thinking about consequences), struggle with organisation, and in some cases may be overly active.

In the general population, ADHD is the most common neurodevelopmental condition in children and adolescents.

- In Australia, around 6 to 10 per cent of children and adolescents are affected.

- Internationally, the figure is about 5 to 8 per cent.

- In adults, ADHD is slightly less common, affecting 2 to 6 per cent of people in both Australia and overseas.

There has been a slight increase in ADHD rates over time, likely due to greater awareness and improved diagnostic criteria.

ADHD is more common in boys than girls, particularly in childhood. This difference tends to lessen with age. The inattentive type of ADHD, which includes difficulties with focus, forgetfulness and disorganisation, is the most commonly diagnosed.

Among people with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), ADHD is much more common. Between 30 and 55 per cent of individuals with TSC may meet the criteria for ADHD. Intellectual disability and ADHD can also occur together.

The main types of ADHD symptoms are:

- Predominantly inattentive type

- Predominantly hyperactive and impulsive type

- Combined type

Hyperactivity and impulsivity often appear early, sometimes before school age. Inattention may not be recognised until the child starts school. A child with hyperactivity might fidget, be noisy, or constantly move around. Impulsivity may show as difficulty waiting their turn, interrupting others or talking excessively. A child with inattention might be easily distracted, forgetful, disorganised, and often lose items like books, homework or clothing.

As people with ADHD get older, symptoms often become more subtle. Teenagers and adults may feel restless, jump between tasks, and have trouble finishing projects. Emotional dysregulation, or mood swings, is also common. While many people experience some of these behaviours occasionally, a person with ADHD experiences them more often and more intensely. These symptoms can significantly affect relationships, learning and work.

Many children with TSC may show behaviours that look like ADHD. These may also be caused by other factors such as intellectual disability, epilepsy, sleep difficulties or enlarged brain tumours called SEGAs. It is important for individuals with TSC who have attention-related difficulties to receive a thorough assessment, so that ADHD or other contributing conditions can be identified and treated.

For more on ASD and ADHD watch this video with Dr Vinita Prasad, Developmental and Behavioural Paediatrician.

Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Mood disorders include depression and bipolar disorder. Anxiety disorders include panic attacks, phobias and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Diagnosis involves symptoms that cause distress or impairment and persist for some time.

It is difficult to know the exact rates of these disorders in individuals with TSC. Most researchers agree that individuals with TSC, with and without an intellectual disability, are at increased risk of both mood and anxiety disorders.

Other Psychiatric Disorders

Beyond those discussed above, other psychiatric disorders include schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, eating disorders and dementia. There is limited research into cases of these disorders in individuals with TSC and it is not clear whether people with TSC have an increased risk of these psychiatric disorders.

Psychotic disorders with hallucinations or delusions can be seen in association with epilepsy, particularly with temporal lobe seizures. If an individual with TSC experiences psychotic phenomenon, particularly visual hallucinatory phenomena, epileptic activity in the temporal lobe part of the brain should be investigated.

There are many different ways to evaluate intellectual ability. Different methods of testing will be suitable for different individuals and different ages.

The intellectual level is made up of both intellectual ability (measured by IQ type tests) and adaptive behaviours (such as self care, daily living skills and ability to communicate).

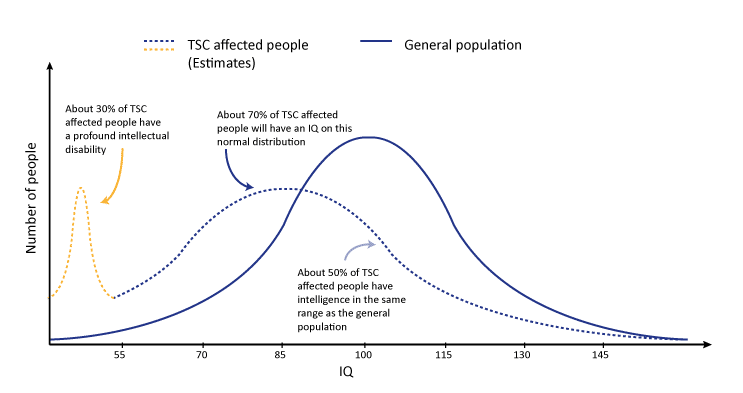

In TSC there is a very large range of intellectual abilities, from very high to extremely low. The graph illustrates this.

Studies of groups of people with TSC have shown that around 50% of individuals with TSC have an IQ score of less than 70, meaning that they have an intellectual disability, which may be mild, moderate or severe. Studies show that up to 30% of people with TSC have a severe impairment.

This research also suggests that around 50% of people with TSC do not have an intellectual disability.

Figure 1: Graph illustrating approximate IQ in TSC affected people vs general population

Understanding an individual’s intellectual level is important to determine their likely support needs in daily life including educational support. It is also important when understanding behavioural difficulties.

Some research studies have also shown that even the most able individuals with TSC can have difficulties with executive skills. Executive skills are those related to how the brain’s 'control centre' works and can include how the brain manages multi-tasking, planning and changing attention. Similar to other ways of assessing intellectual ability, there is not a predictable pattern of what types of executive skills an individual will have difficulties with. Again, this means that individual assessment is very important.

About developmental delay

Developmental delay is a descriptive term used when children under 5 years of age do not meet their developmental milestones. Developmental milestones include talking and walking. We talk about development in 5 areas of development:

- gross motor skills (large body movements from rolling to running)

- fine motor skills (hand eye coordination)

- communication

- learning new knowledge

- self care and social/play skills (interacting with others).

Children with delayed skills in a number of areas which is considered significant may be described as having a Global Developmental Delay. Some of these children may later (when they are aged 5 years or more) be diagnosed with an intellectual disability. This is a cognitive impairment which impacts their function across academic, social and practical functional domains. To make a diagnosis of intellectual disability children will need to complete a psychometric assessment (often called IQ tests) and an assessment of their function in every day life. Deficits in both are required to make this diagnosis. Some children with very significant delay in development and cognition are unable to complete standardised psychometric assessment. Their function can be assessed and a diagnosis of Developmental Disability can be made.

Other disorders which can be described as Developmental Disorders include Autism and Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) because they emerge in the developmental period.

The academic level considers the various learning disorders that can impact how well a person does at school. Studies have suggested about a third of children with TSC that have average or even above average intellectual ability have specific learning difficulties that require support. These students can be overlooked for support and may be considered lazy or stubborn.

This is why it is important to consider academic ability as a specific level and investigate any difficulties with reading, mathematics, written expression or other areas of education. There is no predictable pattern of challenges in individuals with TSC, so it is important to identify individual strengths and weaknesses.

This level refers to the different skills of the brain. These include:

- Executive skills – which include the ability to plan steps in a complex task, to have multiple items in working memory and understanding a concept from multiple points of view.

- Attentional skills – which include choosing what to pay attention to, paying attention for long periods of time and working on more than one task at the same time.

- Language skills – which include understanding language (sometimes called a receptive language disorder) or using language (sometimes called an expressive language disorder).

- Memory skills – which include recognition and recall

- Visuospatial skills – which include navigation, drawing or constructing things.

These skills are usually evaluated by clinical psychologist using standardised measurement tools. Challenges in the above areas may correlate with behavioural challenges in real life.

This level refers to many different factors that influence a person’s quality of life. This includes:

- Self-esteem

- Family functioning

- Parental stress

- Relationship difficulties

All of these factors can be improved through various interventions and support.

There is research that shows high rates of psychosocial difficulties in families with TSC. However not all health professionals may ask about this level. This level is generally covered by the developmental paediatrician, psychiatrist, psychologist and the social worker.

Screening and Assessment for TAND

Screening and Assessment is important because it can lead to early detection and treatment. Each person with TSC should have an individual management plan developed with their medical team that uses the 2021 International surveillance and management guidelines as a starting point.

In September 2023, the TAND Consortium published consensus recommendations for the identification and treatment of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex-associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders (TAND). You can access the publication here.

Understanding the behavioural, psychiatric, intellectual, academic, neuropsychological and psychosocial challenges experienced by someone with TSC is especially important because there is so much variation between different individuals with TSC. TAND may also arise later in life after many years of apparently 'normal' functioning. By understanding the individual’s strengths and difficulties, the best treatment options can be determined.

The TAND checklist is a tool to guide a conversation between a health care professional and the individual with TSC or their caregiver. The checklist is a screening tool, not a diagnostic tool. Using the checklist well should create a priority list and an action plan for the next steps.

The TAND checklist should be completed at diagnosis and at least annually at each clinic visit. Action steps after using the checklist may include:

- the individual, their parents or educators learning more about the disorder;

- conversations with school or education authorities to obtain an individual education plan;

- referral for specialist evaluation and/or treatment.

The Neuropsychiatry panel of the 2012 International TSC consensus conference recommend screening with the TAND checklist at least annually. Areas of concern should lead to next-step evaluations or interventions. Screening could be done with the doctor who co-ordinates the care of the person with TSC such as their GP, paediatrician or neurologist.

Download the TAND checklist

In addition, the panel also recommends comprehensive screening at key developmental stages. These are:

- Infancy (age 0-3);

- Pre-school years (age 3-6);

- Primary School years (age 6-9);

- Adolescence (age 12-16);

- Early adulthood (age 18-25);

and as required thereafter.

In addition, when there are changes in cognitive development or behaviour , a comprehensive assessment should be completed to identify and treat the underlying causes of neuropsychiatric change.

Assessment can involve many different health professionals who may work for different organisations. These might include doctors working in a hospital or private practice, therapists working in an independent centre or teachers working within the child’s school. Different health professionals will have different skills and tools for assessment.

Includes:

- Understanding what screening is;

- What screening is available to everyone within our health system;

- What specific screening is recommended for individuals with TSC.

Management of TAND

Based on the results of individual assessment, an individual management plan should be developed. This plan should be developed in consultation with everyone on “the team”: the individual with TSC and their family along with the health and education professionals involved in their care.

This section describes some of the main options for managing TAND challenges in individuals with TSC. For many of the challenges experienced by a person with TSC the options for management are the same as in a person without TSC.

These might include:

- Education about the disorder(s): Learning more about the specific challenges facing the individual with TSC will usually be beneficial for all family members, carers and the person with TSC. This might include parents, siblings, grandparents, teachers, fellow students, colleagues and respite carers.

- Managing Behaviours: interventions may be particularly effective for very challenging behaviours such as self-injury, aggression and sleep problems. With expert support, even severely challenging behaviours can be reduced, managed or shaped into more appropriate behaviour. Because early intervention is most effective, behaviour management should be instituted early even for minor behavioural challenges.

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): This approach can help an individual identify their own unhelpful behaviours and thoughts and find ways of handling them differently.

- Coaching Techniques: A coach can work with the individual to identify areas of weakness and then work on these as skills to develop. This is a very practical approach that may be helpful to a broad range of people and challenges.

- Psychodynamic therapies: This approach involves a therapist helping a person reflect on their unconscious thought processes that lead to conflict. Options include psychotherapy, family therapy, relationship therapy.

- Autism spectrum disorder management: There are many different strategies that may help to create a learning and home environment that is “autism-friendly”. This might include clear and simple communication, consistent routines and visualized schedules. There are other interventions specifically designed for ASD. It is important to understand that these interventions may have varying amount of evidence on whether they work. Autism organisations can provide more information.

You may want to look at these resources related to Autism:

Medication can have a role to play in treating the TAND challenges in individuals with TSC. It is important to consider how any medication will impact organs of the body that may also be affected by TSC or under stress due to anti-epilepsy medication, such as the heart, kidneys and liver.

It may be useful to consider medication to treat:

- Severe ADHD

- Depression and Anxiety disorders

- Sleep disorders

- Challenging behaviours

Medicines should always be used in combination with other behavioural, educational and other strategies, never on their own.

There is some evidence from clinical trials and research in animal models that mTOR inhibitor medications may have a positive impact on behaviour and learning. This research is still in progress and it will be some time before it is known whether these medicines should be prescribed to treat these difficulties.

The majority of children with TSC will have special education needs. This may involve a mainstream classroom, modified curriculum, technology, additional teaching support, or even a support class within a mainstream school. Children who have a significant intellectual impairment may require a special school.

Individuals with TSC with normal or high intelligence are particularly at risk of struggling in a classroom. This is because they may have specific area of weaknesses that may be “invisible” to the untrained eye. These may include difficulties with attention or dual tasking. This is another way that individual assessment can help.

For more please see TSA's In Safe Hand resources – for families and for teachers and educators.

Last updated: 13 July 2022

Reviewed by: Dr Vanessa Sarkozy, Developmental Paediatrician, Sydney Children’s Hospital Network, Australia and Dr Vinita Prasad, Developmental and Behavioural Paediatrician, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Brisbane

- de Vries, P.J., et al., Tuberous sclerosis associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) and the TAND Checklist. Pediatr Neurol, 2015. 52(1): p. 25-35.

- Leclezio, L., et al., Pilot validation of the tuberous sclerosis-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) checklist. Pediatr Neurol, 2015. 52(1): p. 16-24.

- Kwiatkowski D.J., Whittemore V.H. & Thiele E.A. (2010) Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features, and Therapeutics. Weinheim: Wiley-Blackwell

- Guidelines For The Assessment Of Cognitive And Behavioral Issues In TSC, Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance, viewed 10 May 2012, https://tsalliance.org/pages.aspx?content=589

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder And Tuberous Sclerosis Complex , Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance, viewed 10 May 2012, https://tsalliance.org/pages.aspx?content=582

- TSC and Autism Spectrum Disorders, Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance, viewed 10 May 2012, https://tsalliance.org/pages.aspx?content=604

- Specchio et al., Autism and Epilepsy in Patients With Tuberous Sclerosis Complex- a systematic review article 11 August 2020