What Causes TSC?

TSC (Tuberous Sclerosis Complex) is caused by a change (also known as a mutation) in one of two different genes – TSC1 or TSC2. All of our bodies contain many gene changes, but only some of them are known to cause genetic diseases.

There are two possibilities for how this gene change occurred:

- The gene change was passed on from either the mother or father who also has TSC

OR

- The gene change occurred prior to conception. A mutation may occur in one copy of TSC1 or TSC2 that arises by chance. This is often called a ‘spontaneous mutation’. In this case, it is likely there will be no family history of TSC.

In about 30% of cases TSC is inherited from an affected parent.

This means up to 70% have a spontaneous mutation and the individual with TSC will be the first in the family with the condition.

Genetics is a complex and changing area of medicine.

Clinical geneticists are medical doctors who specialise in genetics and genetic diseases. Genetic counsellors are health professionals who are trained in both counselling and medical genetics. Genetic counselling is a process that can help the whole family understand how TSC is inherited and support you in making decisions about management and reproduction.

It is important that you seek the help of a geneticist or genetic counsellor who will be able to give you advice specific to your situation. A geneticist/genetic counsellor can help you understand how your or your child’s gene change occurred.

Genetics and TSC

Key points to note

- At present it is impossible to predict who will remain only mildly affected and who will be more severely affected by TSC. Even members of the same family can be affected differently. Sometimes, some individuals are so mildly affected that they are not aware they have TSC.

- There are two genes that are known to be associated with TSC. These are called TSC1 and TSC2. People with TSC – regardless of the severity of their symptoms – all have a variation in one of their TSC genes that makes it faulty.

- The pattern of inheritance of the faulty gene causing TSC is described as autosomal dominant inheritance.

- When a parent has a faulty TSC gene copy they have a 1 in 2 (50%) chance in each pregnancy of having a child with TSC.

- In about 30% of the cases, TSC is inherited from an affected parent.

- In the remaining 70% of cases, the person with TSC is the first in the family with the condition. This is likely to have occurred due to a change in one copy of a TSC gene during the formation of the egg or sperm (a spontaneous mutation that occurred for unknown reasons).

- For some people, it is a gene change which results in a group of cells carrying a mutation within the TSC1 or TSC2 gene and another group of cells which does not. This results in a mixture of different cell types, much like a mosaic artwork, hence the name mosaicism.

- The diagnosis of TSC is based on clinical features and genetic testing is usually not required. However, genetic testing for changes in the TSC genes can be helpful in some situations, such as testing a baby in pregnancy for TSC where one of the parents is affected (see below) or testing a baby before enough features have developed to make a diagnosis based on clinical features alone. It is highly recommended that testing be discussed in the context of genetic counselling.

You may like to view this video presentation by Dr Clara Chung, Clinical Geneticist at Sydney Children’s Hospital. It includes:

- mTOR pathway and the TSC genes

- how TSC is diagnosed

- TSC1 vs TSC2

- when genetic testing is useful for a family with TSC

- what does it mean if a gene test for TSC doesn’t find a gene mutation?

- how TSC is passed on within a familyoptions for people with TSC planning a family

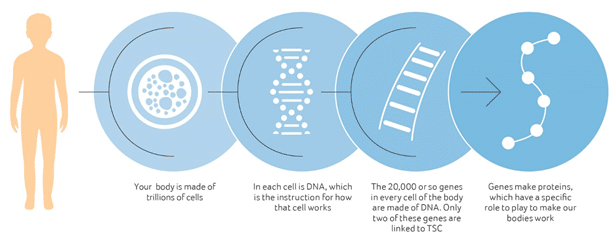

Genes make proteins

Genes make proteins which ensure cells only grow as fast as they need to. TSC1 controls the instructions for creating a protein called harmartin whereas TSC2 controls the instructions for a protein called tuberin.

TSC1 and TSC2 work together to control cell growth. This is why a gene change in either of these two genes can cause a person to have TSC.

The gene change causes cells to grow differently

The TSC gene change stops the gene from producing the protein that the body needs to control cell growth. If these proteins are not produced correctly, some cells can grow in an uncontrolled way resulting in the tumours seen in people with TSC. The tumours that TSC causes are the result of too many cells growing or cells growing more than usual.

When we know that a person has TSC, we can look for the responsible gene change in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes. We find that a TSC1 gene change is found in about one quarter and a TSC2 gene change is found in about two-thirds of people with TSC. Current genetic testing technologies do not find a gene change responsible for TSC in all people with a diagnosis of TSC. In those where a gene change is not found, they are most likely mosaic for TSC (only have a TSC change in a portion of their cells).

Surveillance Needs

- A genetics consultation should be held at diagnosis. This should include obtaining a 3-generation family history.

- Genetic testing and counselling should be offered to you and your family. Note that genetic testing is NOT Medicare rebatable. To have publicly funded genetic testing it is recommended that you see a public genetics service.

Last updated: 29 April 2025

Reviewed by: Dr Clara Chung, Clinical Geneticist, Sydney Children’s Hospital

Updated in 2022 following review by Dr Clara Chung, Clinical Geneticist, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Dr Fiona McKenzie, Clinical Geneticist, Genetic Services of WA, Dr David Mowat, Clinical Geneticist, Sydney Children’s Hospital

2. Northrup H, Koenig MK, Pearson DA, et al. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. 1999 Jul 13 [Updated 2021 Dec 9]. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2022.

3. Giannikou K, Lasseter KD, Grevelink JM, Tyburczy ME, Dies KA et al. Low-level mosaicism in tuberous sclerosis complex: prevalence, clinical features, and risk of disease transmission. Genet Med 2019; 21: 2639–2643.

4. TSC Alliance, How is TSC diagnosed? viewed 20th September 2022.

5. Centre for Genetics Education, Preimplantation genetic diagnosis , viewed 20th September 2022.

Parts of this information have been adapted with permission from copyrighted content developed by the TSC Alliance (tscalliance.org)

There is a large amount of helpful information on the website of the Centre for Genetics Education.